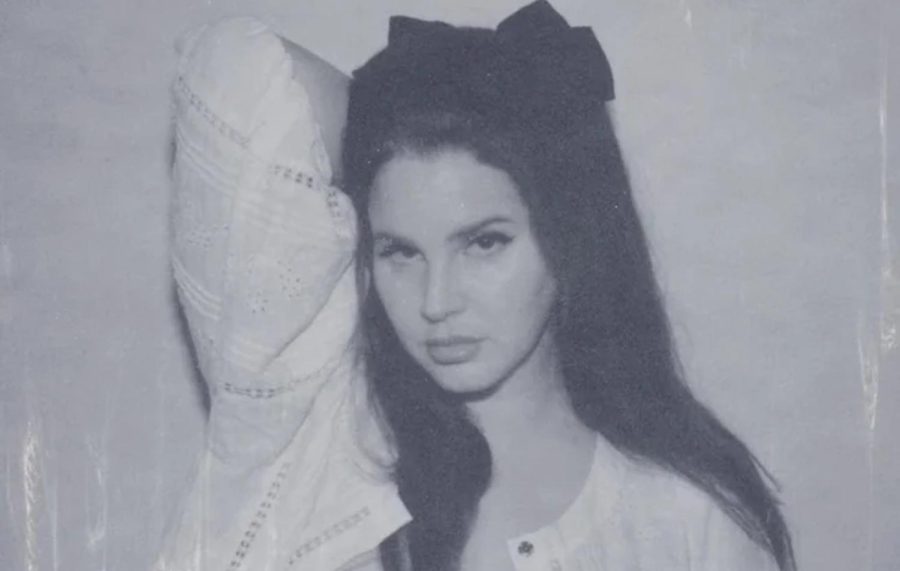

Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd: Album Review

Lana Del Rey’s ninth album boasts an ever-improving songwriting ability, empowerment, and a new outlook.

April 2, 2023

Lana Del Rey has always been multifaceted, both in talent and personality: In fact, her real name is Elizabeth Grant, an identity that very occasionally resurfaces in her records. But altering her persona also raises the question: who is Lana Del Rey?

This question is Del Rey’s biggest challenge, seeing as the answer changes with just about every album she’s released. the intentionally naive femme fatale of Born to Die, a rugged, but intelligent woman scorned on Ultraviolence and an isolated, nostalgic harbourer of feelings on Blue Banisters. But it seems this time, on her lengthily titled Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd, (Which will be referred to as Ocean Blvd for the sake of this review) she doesn’t know, and she also doesn’t care.

As always, the album begins with something that sums up what to expect conceptually. “The Grants”, which likely is titled after Del Rey’s aforementioned real name, opens with a soulful assertion, but not from her. Instead, the intro comes from a backup choir, with a verse that is eventually sung by Del Rey later in the song. “I’m gonna take mine of you with me/Like Rocky Mountain High/The way John Denver sings,” That kind of allegorical, obscure lyricism returns to many of the songs on Ocean Blvd.

Just after “The Grants” comes the title track, a staple of each Lana Del Rey album. Observational and anxious, “Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd” explores her insecurities of being forgotten memoriam, buried under the rubble, much like the secretive tunnel that’s allegedly under Ocean Boulevard. “And I’m like, when’s it gonna be my turn?/Don’t forget me.” She sings again and again, as the beat keeps up with her rising vocals.

Although it is likely intentional that the first two-thirds of the album are strictly piano ballads, with the exception of the latter half of “A&W”, it can become to feel monotonous. This is especially apparent in the sister tracks, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”. Both are beautifully crafted songs that tackle some of the most intimate aspects of Del Rey’s life, but they hold the same long-form, spoken poetry formula, which makes it almost as if they were one continuous, twelve-minute song.

But there are very few tracks that aren’t longer than the average song. The most extended of them all, however, is A&W, which doubles as an acronym for “American Whore” and a reference to the American roadside restaurant of the same name. Even though those two things have nothing to do with one another, they encompass the two most prominent aspects of Del Rey’s entire career: sensuality and nostalgic Americana. Besides the ingenious name, “A&W” is the quintessential Lana Del Rey song. She manages to maintain her opus of romanticism for toxic relationships and environments, while also shedding any ability to be criticized for it. The first part of the song, titled after the track’s acronym, is a slow, introspective acoustic delve through Del Rey’s newfound carelessness. “It’s not about having someone to love me anymore/No, this is the experience of being an American whore,” She explains. Sonically, this is sharply contrasted by the second part, titled “Jimmy”, which comes to be through a warping, hip-hop-inspired transition. What’s most interesting, however, is this isn’t the first time Jimmy has made an appearance in her music. On the Ultraviolence title track, Jimmy is heard of as an abusive ex who is the muse for her work. It seems that nearly a decade later, Del Rey has moved into a new plain of confidence against him. “Your mom called, I told her, You’re f***king up big time/But I don’t care, baby, I already lost my mind.” She sings. To add to the “Early America” aesthetic of the song, Del Rey interpolates the lyrics to the popular 1959 Little Anthony song titled “Shimmy Shimmy KO KO Bop”, But of course, with her twist. Instead, she sings “Jimmy Jimmy, cocoa puff”.

More highlights from the album include “Paris, Texas” which can only be described as a dream-worthy lullaby, “Let The Light In” a story-telling love song featuring Father John Misty, and the reclaiming and symbolic “Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep-sea fishing”, which is not even the longest of her song names. (that title belongs to her 2019 album Norman F*****g Rockwell’s “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but I have it”)

Even the smallest details of Del Rey’s ninth album add to its character. From the almost comical sample from Tommy Genesis on “Peppers” to the spoken portion of “Taco Truck x VB” by Margaret Qualley, (the fiancé of Del Rey’s primary collaborator, Jack Antonoff) this is, certifiably, the most “Lana Del Rey” album yet. Even the interludes contribute something: “Judah Smith Interlude” contains a pastor cleverly singing the praises to Del Rey’s talent, and “Jon Batiste Interlude”, which comes just after his soul-pop duet on “Candy Necklace”, just has him and Del Rey laughing in between vocalizing.

Despite the serious, deeply personal nature of many of the songs on Ocean Blvd, Lana Del Rey couldn’t sound any more flippant. It seems she has reached a point in her life (and career) where she’s willing to create art surrounding less of her persona and more of her experiences, while having fun with it.

Grade: A+

Listen Here!